What a “good baseline” usually means

In practical terms, many evidence-aligned patterns converge on similar features: plenty of plants, adequate protein, fiber-rich carbohydrates, and fats that aren’t dominated by ultra-processed sources.

Food patterns, nutrients, and supplement reality—explained like an encyclopedia, not a sales pitch.

Nutrition influences the eyes through two main channels: (1) the health of the retina and supporting tissues, and (2) systemic factors—especially vascular and metabolic health—that show up in the eyes over time.

It’s also a topic with a lot of noise. Some nutrients matter, some claims are exaggerated, and supplements are often discussed as if they are universally helpful. In reality, the strongest evidence is usually about patterns (overall diet quality and long-term metabolic health) and about a few condition-specific supplements rather than “everyone should take X.”

Why “one superfood” rarely outperforms a strong baseline pattern.

Eye nutrition discussions often start with individual nutrients—vitamin A, lutein, omega-3s—because they are easy to package as a headline. But the most reliable long-term signal is typically overall diet quality: adequate protein and micronutrients, a high fraction of minimally processed foods, and good long-term metabolic control.

This matters because the retina is metabolically demanding and highly vascular. The same factors that harm blood vessels and nerve tissue elsewhere—poor glycemic control, hypertension, smoking—also affect ocular tissues. In that context, nutrition is less a “retina hack” and more part of a long-term risk profile.

In practical terms, many evidence-aligned patterns converge on similar features: plenty of plants, adequate protein, fiber-rich carbohydrates, and fats that aren’t dominated by ultra-processed sources.

Claims that a single supplement “improves eyesight” for most people are usually overstated. Comfort issues can be influenced by hydration/environment, but structural eye diseases typically require clinical evaluation.

Nutrition and systemic health show up strongly in conditions tied to vascular or metabolic issues, and in certain age-related conditions where specific supplement formulas are used in a targeted way.

Not because they’re magic, but because they map to real biology.

The eyes use a wide range of nutrients—this isn’t a “three vitamin” system. That said, several nutrients are repeatedly discussed because they relate to oxidative stress management, retinal function, and tissue maintenance. The practical takeaway is that deficiencies matter, and dietary patterns that reliably deliver micronutrients tend to correlate with better outcomes than narrow supplement stacking.

Vitamin A is essential for phototransduction (the process of converting light into signals). Severe deficiency can cause night-vision problems, but in most developed settings deficiency is uncommon. Carotenoids are also discussed for their role as dietary pigments with antioxidant behavior.

These show up in antioxidant discussions and in certain supplement formulas used for specific conditions. Their relevance is often framed around oxidative stress, but supplementation is not automatically appropriate for everyone.

Omega-3s are commonly discussed in the context of tear film, inflammation signaling, and overall cardiovascular health. Their role in dry eye discussions is active, but results can vary and are not a substitute for evaluation.

Two pigments frequently discussed in macular health and diet quality.

Lutein and zeaxanthin are carotenoids that accumulate in the macula (the central part of the retina responsible for detailed vision). They are often described as part of the eye’s “built-in filter” system because they absorb certain wavelengths and are studied in the context of oxidative stress and retinal aging.

In practice, they are less a stand-alone intervention and more a marker of plant-rich dietary patterns. Leafy greens and certain colorful vegetables are commonly cited sources, but the larger point is that diets rich in diverse plants tend to deliver multiple supportive compounds at once.

Dry eye conversations, inflammation signaling, and the difference between comfort and disease.

Omega-3 fatty acids are often discussed in eye health because the ocular surface is sensitive to inflammatory signaling and because overall vascular health is strongly tied to long-term eye outcomes. Many people encounter omega-3 content through dry eye discussions, where the goal is comfort and tear film stability rather than “curing” a disease.

The practical interpretation: omega-3s are a plausible piece of a broader plan for some people, but outcomes vary and the topic is not settled in a way that supports universal claims. If symptoms are persistent, the more reliable approach is evaluation: identifying meibomian gland dysfunction, environmental drivers, medication side effects, and other contributors.

For the non-nutrition side of this story, see Habits (comfort drivers) and Digital Life (near-work + screen comfort).

One of the clearest examples of “supplements can matter, but not for everyone.”

The AREDS/AREDS2 supplement formulas are commonly referenced in macular degeneration (AMD) discussions. This is an important point: these formulas are not positioned as general “eye vitamins.” They are used in a targeted way in the context of specific AMD risk categories, and the decision is ideally made with an eye care professional based on clinical findings.

This is a pattern you’ll see repeatedly in eye health: the most meaningful supplement evidence tends to be tied to a defined clinical scenario, not general wellness claims. When a supplement is truly supported, it usually comes with specifics: which people, which stage, which dose, and what outcome it changes.

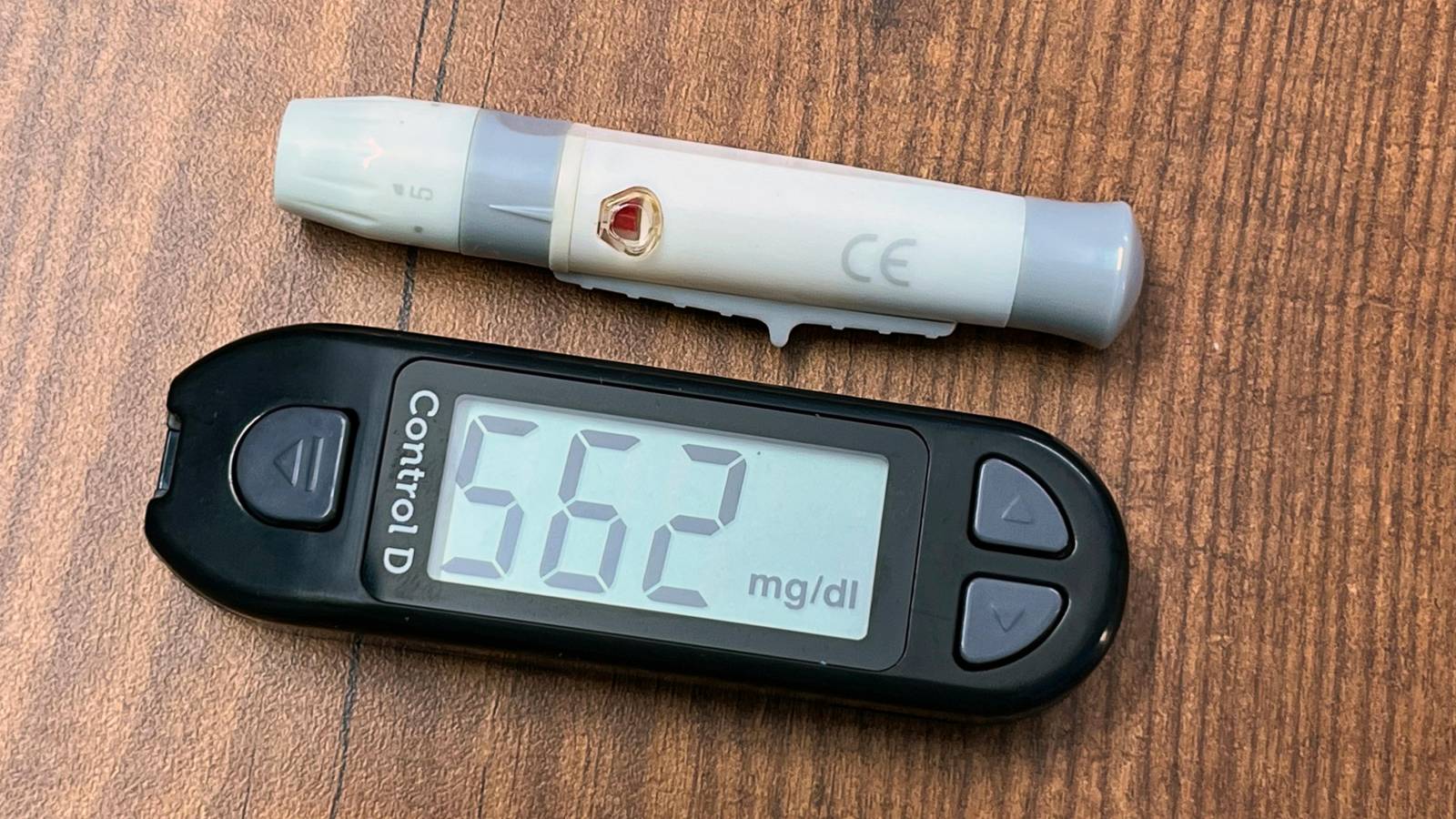

Why eye health discussions often return to diabetes, blood pressure, and smoking.

The eyes are not isolated from the rest of the body. The retina depends on stable blood flow, healthy capillaries, and a tightly controlled internal environment. This is why diabetes and hypertension have well-known eye complications and why many long-term eye outcomes correlate with cardiovascular risk factors.

From a nutrition standpoint, the point is not a single “retina nutrient.” It’s that long-term dietary patterns and metabolic control are strongly tied to risk. In an encyclopedia framing: nutrition supports the system that the eyes depend on.

Where they fit, common pitfalls, and why quality and context matter.

Supplements are appealing because they feel precise—one pill for one outcome. But eye health rarely behaves that way. When supplementation is supported, it tends to be in a defined context (example: stage-specific formulas for AMD), and it tends to be one component of broader management rather than a replacement for care.

Correcting a deficiency, supporting a condition with an evidence-based formula, or filling a known gap when diet is constrained. These are structured scenarios with clearer rationale.

“More is better,” overlapping products that duplicate ingredients, and assuming “natural” means risk-free. Interactions and side effects are real—especially at higher doses.

Look for specifics: who was studied, what outcome changed, and whether results were clinically meaningful (not just a lab marker). The Research & Tech page will include a simple “how to read studies” guide.

Short answers, with enough context to be useful.

Carrots are associated with vitamin A, which is essential for vision. The myth becomes exaggeration when it implies that carrots improve vision for most people beyond supporting normal function. Severe deficiency is where vitamin A becomes a dramatic issue; otherwise, the bigger story is overall diet quality.

Usually not. The strongest supplement evidence is typically condition-specific (for example, AMD formulas), and the best choice depends on diagnosis, stage, and individual risk. “Eye vitamin” is marketing language unless it is tied to a defined clinical use.

Nutrition supports long-term risk and comfort factors, but it does not substitute for diagnosis, monitoring, or treatment when disease is present. If symptoms are new or persistent, an evaluation is the correct next step.